Quensel’s career model describes crime as a process that can evolve from a small insignificant offence to a serious criminal career due to the failed interaction between the individual and the environment (including judicial sanctioning).

Main proponent

Theory

With his model, Quensel wants to combine the etiological and penological perspective, while at the same time not viewing criminality as the result of a single event, but as a multi-phase process. As an example, he draws on juvenile delinquency, which, according to Quensel, develops over several years, and which is the result of failed interaction between the juvenile and his environment (including the state sanction apparatus).

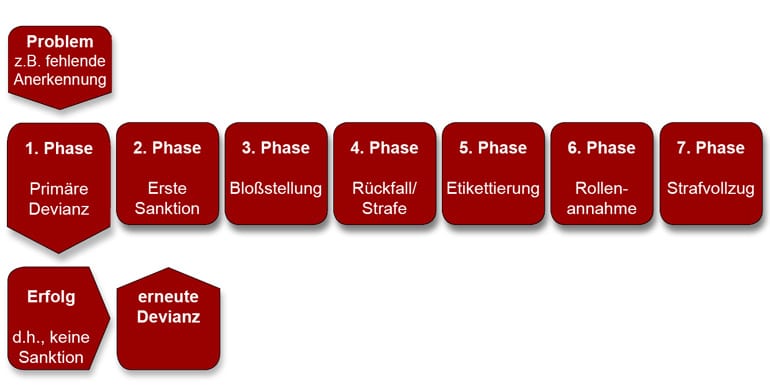

Quensel’s approach, therefore also called the “vicious circle model”, proceeds as follows:

In the first phase, a mostly small, first offence is committed in order to solve a certain, mostly small, problem: Lack of recognition in the peer group, school failures, etc. Now the crime can either turn out positively, i.e. succeed, then the problem has been solved in some way and serves as reinforcement for possible future delinquency. Or it cannot succeed, then the young person can either be lucky and not caught, or he can be unlucky and officially punished.

If the latter is the case, we are in the second phase of Quensel’s career model: the young person has to serve detention, he is reprimanded or perhaps even has to be placed under juvenile detention.

In the following third phase, it becomes increasingly difficult for the young person to solve his actual problem, as it has been amplified by the sanction and the mere presentation in public as a deviant. The delinquent experiences social rejection, feels that punishment is unjust, and finally finds confirmation and recognition in other dissenters.

This often leads to other deviant action, which then initiates the fourth phase of the model. Society and the judiciary recognize the young person as a repeat offender; in their view, the sanction has apparently not worked and must be intensified. This leads to serious judicial reactions and an increase in social rejection.

A subsequent process of building up further offences and increasingly harsh punishments then leads the young person into the fifth phase, in which, after Quensel, he is now labelled as a delinquent and treated accordingly: He loses his apprenticeship, is not allowed to obtain a driving licence or is otherwise restricted in his freedom of action. Accordingly, he begins to incorporate the definition of the deviator into his own self-image.

In the sixth phase, the delinquent becomes an outsider, only the deviant group still offers social contact. Certain criminal techniques are internalized, the role of the delinquent is fully accepted and one’s own actions are now considered normal and correct.

In the seventh phase, the criminal finally ends up in a prison that aggravates or confirms both his problems and his self-image, as well as his public image. The juvenile now identifies completely with his delinquent role.

The “vicious circle” comes to an end in an eighth phase: after release from prison, the labelling of the now officially convicted person is tightened by the social environment. Old employers, friends and possibly also family members turn away, the proximity to other previous convicts is looked for. If delinquency occurs again, the previous conviction aggravates the sentence.

Implication for criminal policy

Quensel’s career model focuses primarily on problematizing the societal reaction to criminal behavior (and is thus close to the labelling approach). What is crucial here is that delinquency and its sanctioning are seen as representative of other underlying conflicts and problems (e.g. conflicts with parents, teachers, friends or colleagues).

Particularly critical is the intervention of the judiciary and the resulting selective restriction of the punished person’s actions. The delinquent, instead of being constructively taken care of, is pushed into social isolation; he is stigmatized and thus learns defense and behavioral techniques that promote his criminal career. In doing so, Quensel specifically addresses the disproportion between the criminal and the state institutions. The public and bureaucratic judicial apparatus is completely alien to the former. He does not understand it and distrusts it. Similarly, the members of this apparatus do not know and mistrust the youth world. Official bodies, however, are forced to play their role as judges, social workers, etc., which is alien to the delinquent and which, in the final analysis, must not show solidarity with the delinquent. In this way, rapprochement and mutual understanding can hardly take place. Moreover, both sides have had bad experiences with each other over a longer period of time and are therefore not prepared to step out of their own world and their own role.

Quensel therefore calls for more sociological fantasy in relation to the development of criminal careers (caused by social grievances and a lack of support for young people) and more social psychological influence during and at the end of the phase model (prevention of the process of building up, countermeasures to take on the delinquent role model).

Critical appreciation & relevance

Quensel’s career model is to be appreciated as a differentiated example of Lemert and Becker’s approach of the forcing effect of judicial reactions, taking into account the causes of primary deviance. It is described here in great detail and comprehensibly how a minor offence can lead to a genuine criminal career through the reaction of the environment and the state alone.

If one considers the specific age distribution in criminal activities, according to which almost all juveniles become deviant at some point, the model is still topical from today’s point of view, as it emphasises the importance of an independent juvenile criminal law and its conceptualisation, which is more geared to education and problem solving.

It is questionable, however, whether the cause of the first deviating action is in fact always only an attempt to solve the problem.

In addition, in Quensel’s model, the young person, after his unique delinquency, appears too much as a pure victim and plaything of justice or social rejection. As in Henner Hess’ career model, however, it should be noted that the delinquent always has the opportunity to break out of his negative development and consciously choose an alternative to the path described here.

Literature

Primärliteratur

- Quensel, Stephan (1970): Wie wird man kriminell? In: Kritische Justiz 1970, 377ff. Frankfurt am Main.