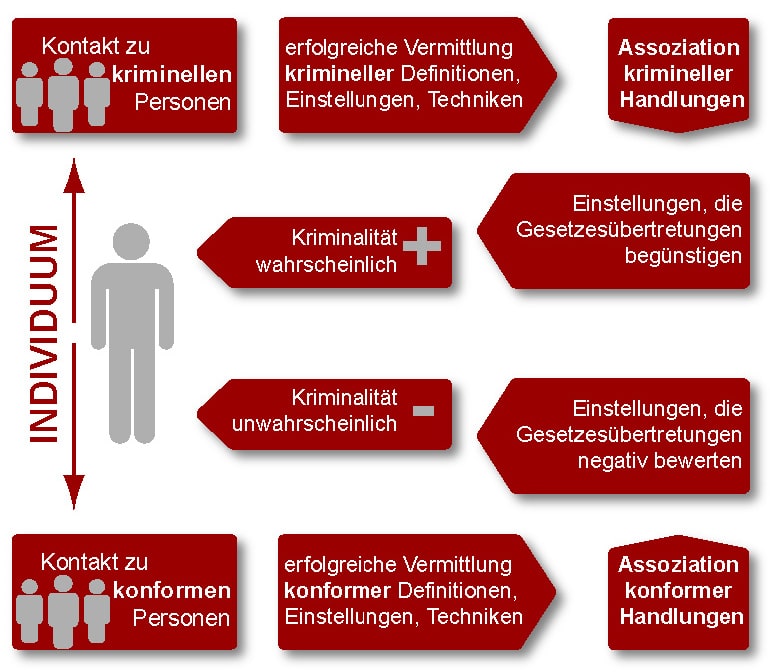

In his theory of differential association, Edwin Sutherland proposes that criminal behavior is learned. A person will become delinquent if there are prior attitudes that favor law breaking, as opposed to attitudes that evaluate law breaking negatively.

Main proponent

Theory

Edwin Sutherland’s theory of differential association posits that criminal behavior is learned through contact with people who are themselves criminals.

It is therefore called the “theory of differential contact”. The term “association”, however, refines this idea by recognizing that it is not enough to simply be exposed to criminal individuals, but that these contacts must also successfully convey criminal definitions and attitudes.

The basic thesis here is that criminal behavior is learned when more pro-violence attitudes are learned than anti-violence attitudes. Conversely, learning criminal attitudes, motives, and definitions becomes more likely the more contact there is with people and groups who violate the law and the less contact there is with people and groups who live by the rules.

To put it simply, contact with criminals leads to criminal behavior by modeling criminal behavior. This is even more likely if there is less contact with non-criminals.

Sutherland’s theory of differential contacts (see diagram) is based on nine theses which summarize the theory of differential association:

- Criminal behaviour has been learned.

- Criminal behaviour is learned in interaction with other persons in a communication process.

- The learning processes take place primarily in small and intimate groups (and thus less through (mass) media, for example).

- The learning of criminal behaviour includes the learning of techniques to commit a crime as well as specific motives, rationalisations and attitudes that favour criminal behaviour.

- The specific direction of motives and drives is learned by defining laws positively or negatively.

- A person becomes delinquent as a result of the predominance of attitudes that favour the violation over those that take a negative view of the violation.

- Differential contacts vary according to frequency, duration, priority and intensity.

- The process of learning criminal behaviour includes all the mechanisms involved in any other learning process.

- Although criminal behaviour is an expression of general needs and values, it is not explained by them. Non-criminal behaviour can also infer from exactly the same values and needs (e.g. sexual urges).

Implication for criminal policy

Sutherland’s theory of differential association represents a rehabilitative ideal. Since criminal attitudes and activities can be learned, they can be logically deduced and unlearned, or compliant behavior, attitudes, and rationalizations can be achieved in the first place.

In the sense of the theoretically decisive imbalance between associated attitudes that favor violations of the law and attitudes that evaluate violations of the law negatively, it must therefore be the goal of justice and society to surround criminals with non-criminals or to dissolve social spaces in which predominantly people with deviant motives and patterns of action live.

Furthermore, criminal law must build on the ideal of rehabilitating offenders.

Critical appreciation & relevance

In the past, Sutherland has often been accused of having theoretical gaps in his concept, for which other theories or theoretical extensions have been developed.

For example, Sutherland himself drew attention to the different needs and preferences of learning individuals, which contribute significantly to whether deviant actions and attitudes are accepted or not.

However, Glaser pointed out that it is not the number of people with deviant attitudes that is crucial for learning crime, but rather the degree of identification with one or a few people.

Cloward and Ohlin pointed out that access to illegitimate means or exclusion from legitimate means is a crucial factor.

Akers (and also Eysenck) extended Sutherland’s theory to include a detailed analysis of the learning processes that take place (conditioning, social learning/observing a model, etc.).

Nevertheless, Sutherland’s theory of crime-related learning has to contend with the charge of partial tautology, since the existence of the crime must already exist in order for it to be passed on in the first place.

Furthermore, the theory of differential associations does not take into account instinctive and affect crimes, nor does it take into account the fact that the cognitive abilities of different individuals may also vary.

Sutherland’s thesis also takes a purely behaviorist view: People respond automatically and reflexively to stimuli in the environment. Cognitive or unbiased aspects are not sufficiently considered here, but Sutherland’s theory can be seen as a far-reaching anti-biologistic theory. According to Sutherland, the consideration of social processes in the search for the causes of crime has only just begun to take its course and has certainly long since become dominant in criminological research alongside social-structural aspects. The idea that crime can be learned has transformed the previously very perpetrator-oriented perspective into a sociological and socio-psychological one.

Literature

- Edwin H. Sutherland (1924): Principles of Criminology. Auflage von 1966, mit Donald R. Cressey, Philadelphia.