Classical Criminology sees criminal action as the result of free and rational decisions of the acting individuals.

Main proponents

Cesare Beccaria, John Howard, Jeremy Bentham, Samuel Romilly, John Anselm von Feuerbach, Sir Robert Peel, Samuel Pufendorf u.a.

Theory

Classical crime theory, especially according to Beccaria, is based on the assumption that people are free of will and thus completely responsible for their own actions, and that they also have the ability to rationally weigh up their abilities. Crime is therefore the result of free and rational decisions of the acting individuals.

Although social conditions are also mentioned as causes of crime in the classical period, Beccaria and others are more interested in the crime than in the perpetrator. This is due to the idea of equality of all human beings, as well as to the fact that any social (or at the beginning of the classical period also supernatural) circumstances can be met equally, which means that only the deed itself distinguishes the criminals from the non-criminals.

Implications for Criminal Policy

The central demand of the classical school of criminolgy is the proportionality of the sanctions to its preceding crimes. According to Beccaria, the level of punishment must be based on the damage caused. The arbitrary use of justice and overly harsh and inappropriate punishments should be rejected. It is necessary to introduce clear, legal and equal rules for everyone with regard to punishment and the severity of penalties, which should not be based on the person committing the crime but only on the act itself. Therefore, for the same crimes, there must be consistently the same penalties, which in turn must be strictly bound to the written, precise definitions of the various crimes and their corresponding criminal regulations.

The call for punishment and less cruelty came not only from Beccaria. Romilly opposed the arbitrary imposition of harsh and disproportionate punishments, Peel called for the necessary secularization and rationalization of criminal law, Feuerbach advocated the abolition of torture, Pufendorf introduced the concept of human dignity into criminal law, and Howard achieved prison reforms that took into account the health and hygiene of prisoners.

Almost all criminologists from his time period also called for the more or less extensive abolition of the death penalty. However, Beccaria and other authors referred above all to the often disproportionate nature of this sanction to their crime. Many people were then executed for less serious crimes or even killed unjustly. Beccaria wanted to fight this grievance.

However, a stance which in principle is opposed to the death penalty – as it now prevails in many countries, particularly in Europe – cannot be associated with the classical school of criminology, even though they have often been interpreted in this way in the past. After all, Romilly, Feuerbach and Beccaria referred to offences that would still be eligible for the death penalty.

This phenomenon can be explained by the demand for the preventive effect of criminal law, which emerged at the time. According to Beccaria, punishment may only be used if and when it serves to prevent crime. Since man is seen as a free and responsible being, deterrence is the only imaginable form of crime prevention.

The first consequence of this is that secret trials must be abolished and court proceedings accelerated in order to discourage the apparently high level of crime investigation and effective suspension of justice. It also follows, however, that certain particularly serious crimes must continue to be punishable by the death penalty in order to comply with the requirements of proportionality and prevention.

However, Beccaria stresses that the vast majority of criminal offences should be punishable by imprisonment, since too frequent use of the death penalty leads to brutalisation of society and therefore no longer has a deterrent effect.

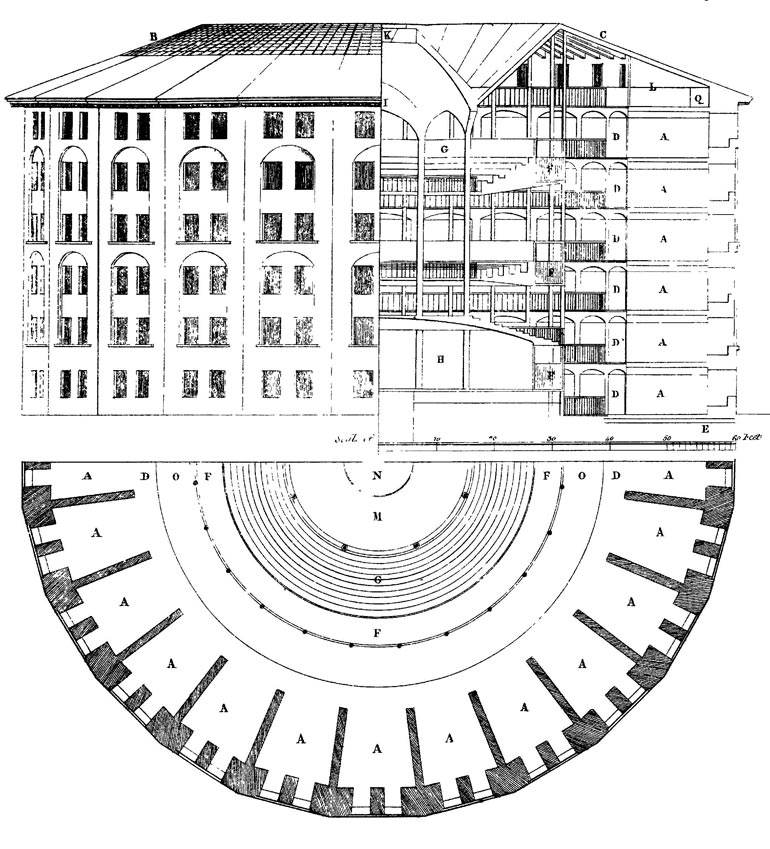

The deterrence hypothesis on the one hand and the underlying assumption of human rationality and responsibility on the other are also reflected in Bentham’s idea of the Panoptikum, a prison in which the inmates, due to the construction of the building, are at all times under the visual surveillance of the guards or must assume that this is the case. According to the tradition of classical criminology, Bentham assumes that this form of constant surveillance must lead to a conformist way of life for the prisoners within the walls, since it would be extremely irrational to behave criminally in the conscious presence of a guard. Even more than Beccaria, Bentham can be seen here as the implicit precursor of the ‘Rational Choice’.

Critical Appraisal & Relevance

It is certainly problematic that the question of the phenomenon of “crime” in the classical period was probably still a by-product of the political and literary handling of punishment and justice. There was no such thing as a specially developed classical theory of crime. The classical theory of crime is rather a summary of the mostly political ideas of Beccaria and his contemporaries, presented and interpreted in retrospect by recipients. Thus there are quite a few who date not classical but positivist criminology as the actual beginning of today’s criminology, since there the subject of “crime” is clearly outlined.

However, the significance of Beccaria and classical criminology (in addition to their influences on crime policy) can be justified above all by their diverse current perceptions (rational choice, deterrence, routine activity approach). Thus, the classical school is not only the oldest school, but probably also the most constant, whose relevance is repeatedly confirmed in neoclassical studies.

In terms of content, classical theory weakens the incompatibility of the assumptions that although people are free and responsible for their actions, they are at the same time subject to (supernatural, later social) causes that lead to their deviant behaviour. However, this contradiction is again due to the fact that Beccaria and Co. did not pursue a coherent crime theory, but tried to justify their political and criminal demands theoretically. On the one hand, it was necessary to mention society as the focus of criminal activities in order to achieve a certain understanding of the perpetrator and thus a renunciation of excessively harsh punishments (this was also associated with criticism of the judges and the judicial proceedings). On the other hand, the emphasis on the equality and freedom of all human beings was also important in order to underline the utilitarian and enlightenment thought prevailing at that time and to establish it in criminal law.

A theory-related critique can therefore be better carried out on the basis of deterrent and rational electoral theories.