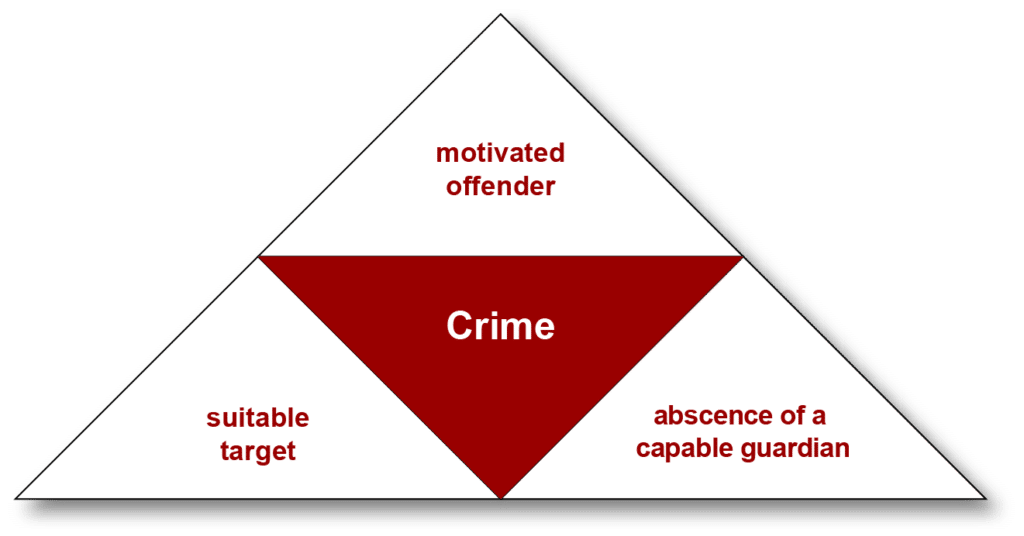

The Routine Activity Theory states that the occurrence of a crime is likely if there is a motivated offender and a suitable target, with the simultaneous absence of a capable guardian.

Main proponents

Lawrence E. Cohen, Marcus Felson, Ronald V. Clarke

Theory

According to Cohen and Felson, crime rates depend on the constantly changing lifestyles and behaviours of the population. Depending on the time and place, three factors that are decisive for Cohen and Felson and are responsible for the occurrence or absence of criminal behaviour vary (see diagram).

Accordingly, the requirement for crime is a offender motivated to commit a crime, whereby this motivation can be of very different nature.

Then there must be an object suitable for the offender (potential victim, tempting object, etc.). There are various factors that influence whether the object is suitable: value, size/weight and visibility of the object as well as access to the object.

Last but not least, the lack of informal or formal control should be mentioned as protection for the object of the crime. This can be personal control, but also technical control: police officers and security personnel, video surveillance and alarm systems, attentive passers-by, neighbours, friends and staff.

In summary, the Routine Activity Theory describes crime as a situational event that depends less on the offender’s personality and socialization than on the situation in which the offender finds himself.

Implications for Criminal Policy

The criminal policy consequence of Rational Choice Theory, of Deterrence Theories, but above all of the Routine Activity Theory is the so-called Situational Crime Prevention.

This form of criminal policy does not attempt to prevent future crime by rehabilitating, deterring or segregating the perpetrator, but rather by reducing the contextual and situational possibilities for crime. The task of politics is therefore to change our common living environment in such a way that the number of opportunities to commit crimes is reduced.

In a later extension, Clarke and Eck (2005) extended the approach to 25 techniques of situational crime prevention. In addition to the theoretical foundations mentioned above, the reference to Sykes’ and Matza’s techniques of neutralization is noticeable here (see 5th column of the table: Reduce Excuses).

25 Situational Prevention Techniques

| Increase the effort | Increase the risks | Reduce the rewards | Reduce provocations | Remove excuses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Target harden

| 6. Extend guardianship

| 11. Conceal targets

| 16. Reduce frustrations and stress

| 21. Set rules

|

2. Control access to facilities

| 7. Assist natural surveillance

| 12. Remove targets

| 17. Avoid disputes

| 22. Post instructions

|

3. Screen exits

| 8. Reduce anonymity

| 13. Identify property

| Reduce temptation and arousal

| 23. Alert conscience

|

4. Deflect offenders

| 9. Use place managers

| 14. Disrupt markets

| 19. Neutralize peer pressure

| 24. Assist compliance

|

5. Control tools/weapons

| 10. Strengthen formal surveillance

| 15. Deny benefits

| 20. Discourage imitation

| 25. Control drugs and alcohol

|

(Clarke, 2005, p. 46f.)

It is also worth mentioning Clarke’s demand that the judicial system should only be used as a last resort. The focus should be on natural strategies for situational crime prevention, so that it seems convenient and sensible for people in individual situations to behave in a legal manner. An example of this would be an appropriate parking policy aimed at preventing illegal parking.

Critical Appraisal & Relevance

The Routine Activity Theory can be appreciated as a theoretical basis for the first time no longer purely perpetrator-oriented concept of Situational Crime Prevention.

Their success in reducing crime has been proven in numerous studies. However, situational crime prevention has to face the criticism of offence shifting, after which crime does not decrease, but merely shifts to temporal, spatial, methodological and other dimensions. Critics also warn that by concentrating on situational factors, the actual root causes of crime remain untouched.

In addition, the routine activity approach suffers from the same weaknesses as the rational choice theory and the deterrence theories: because there, too, a rational and therefore deterrent person is assumed, but emotional, psychological, social and developmental factors are ignored.

Finally, it could be argued that situational criminal policy stands for a conservative world view characterized by the call for more surveillance and the exclusion of marginalized social groups. Moreover, the “clinical” view of crime as the result of inadequate protection against situational risks does not allow for an empathetic attitude toward crime victims (who, according to this view, have failed to “manage” the risks of crime sufficiently).

Literature

- Clarke, R. V. (2005). Seven misconceptions of situational crime prevention. In: N. Tiiley (Ed.). Handbook of Crime Prevention and Community Safety (pp. 39-70). London: Routledge. URL: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781843926146.ch3

- Clarke, R. V. & Eck, J. E. (2005). Crime analysis for problem solvers: In 60 small steps. Washington DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing.

- Clarke, R. V. (1993): Routine activity and rational choice. New Brunswick, NJ.

- Clarke, R. V. (1995): Situational crime prevention. In: Michael Tonry: Building a safer society: strategic approaches to crime prevention. Chicago.

- Cohen, L. E.; Felson, M. (1979): Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44 (4), pp .588-608.