What is criminology?

Criminology derives from the Latin word ‘crimen’ (crime) and the Greek word ‘logos’ (doctrine). The “invention” of the term criminology (here: criminologia) is attributed to the Italian scholar Raffaele Garofalo, who published the book “Criminologia: Studio sul Delitto, Sulle sue Cause e sui Mezzi di Repressione” in 1885. The British criminologist David Garland (2002) states that the historically still relatively young discipline of criminology can be characterized by two essential core areas. This is on the one hand a “governmental project” and on the other hand the “Lombrosian project”. Behind the first category lies a criminology that has dedicated itself to administrative purposes and records the development of crime in empirical studies and evaluates the work of state institutions such as prisons or the police. The Lombrosian project goes back to the Italian psychiatrist and prison doctor Cesare Lombroso, who is regarded as the founder of an empirically founded (positivist) criminology. Through studies on prisoners, Lombroso wanted to determine the nature of criminals and thus determine the causes of crime (see below). Garland further notes that these two areas have increasingly overlapped and merged in recent times.

Definition

Criminology can therefore be defined as the study of crime. Criminological knowledge is created both theoretically and empirically (i.e. in the form of scientific studies).

The Latin word crimen, however, not only stands for crime, but can also be translated as accusation (it is derived from cernere – select, decide -). Criminology therefore deals not only with behaviours that we perceive as crimes, but also with the question of which behaviour, when and why are perceived as criminal. These two perspectives become clearer when we take a closer look at the subject of criminology.

What is the subject of criminology? – The concept of crime

The concept of crime from a legal perspective

At first glance, the question of what a crime is seems easy to answer: namely, all actions that violate a criminal law. In Germany this is regulated in § 12 of the StGB. Here it says that crimes are unlawful acts which are at least punishable by imprisonment of one year or more. Misdemeanours are unlawful acts which are at least punishable by a lesser prison sentence or which are punishable by a monetary penalty.

If you now look at individual legal norms, it is clear that, for example, counterfeiting (imprisonment for not less than one year) is a crime, pimping (imprisonment for between six months and five years) is a misdemeanour, and so on. Actions that are not covered by any law (e.g. feeding gremlins after midnight) cannot constitute crime or misdemeanour following the principle of law nulla poena sine lege. Despite its unambiguousness, this concept of criminal crime is insufficient from a criminological point of view.

The concept of crime from a criminological perspective

The initially plausible definition of crime according to the Criminal Code must, however, be further differentiated if one considers the object of criminology – i.e. the crime. We all use the term and it seems to us to be plausible at first, without further reflecting on its meaning. If you asked someone to define what a crime is, that person would probably conclude that a crime is an act that violates a penal code. However, this legalistic approach – although found in many criminology books – is useless; this definition means that no crime can exist if there were no criminal law. Certain acts, however, seem to us to have a great wrongfulness that we would judge as evil, morally reprehensible or unjust even without legal background knowledge. But where is the line between criminal on the hand and and undesirable acts on the other? Whose value judgement do we take into account – that of the majority of society, that of the smartest, richest, loudest members of a community?

Crime has no ontological reality, no fixed and unchangeable nature. Unlike, for example, a table, which can be described as a physically present object by a tabletop, four table legs and a fixed purpose and use. By contrast the concept of crime is an attribution. The table has its own “table-like” nature – regardless of whether it is described as such or used. A crime, on the other hand, only becomes a crime through its designation, and that people behave accordingly to it. Certain acts are called crimes. However, this is not a quality of the corresponding actions per se. Which actions are referred to as crimes is subject to historical and cultural change. Crimes are therefore social constructs. This thought, which may initially appear abstract, becomes clear when we look at examples:

-

Mugshot of Al Capone (1931) In the years 1920 to 1933 alcohol prohibition applied in the USA. The production, transport and sale of alcohol was prohibited. Those who circumvented prohibition committed a crime and were punished. Despite the prohibitions, many Americans did not want to give up drinking and found themselves in so-called speakeasies, which illegally served alcohol or they illegally produced their own moonshine. Providing alcohol for the Americans who were willing to drink proved to be a financially lucrative field of activity for organized crime. Men like Meyer Lanski or Al Capone became rich and public enemies of the state through alcohol smuggling. Alcohol prohibition is difficult to imagine from today’s perspective. Alcohol consumption is widespread in our culture and a ban could hardly be enforced (just like eighty years ago in the USA). The example shows, however, that it is not the intrinsic quality of an action (drinking alcohol) that constitutes a crime, but the social attribution (alcohol is bad, ergo: alcohol is banned from now on).

- Other examples show that cultural change has also taken place in Germany, including a change in actions that were or are perceived as crimes. From 1871 to 1994 German law made homosexual acts between men a punishable offence (it is also interesting to note that only men are mentioned in § 175 StGB). In the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, during the period of National Socialism and also in the Federal Republic of Germany, many tens of thousands of men were criminalized, persecuted, punished and (during the Nazi era) deported to concentration camps. It is obvious that a sexual preference is not a crime per se. A look at history shows that especially in the field of sexuality, moral concepts are often the subject of social controversies and continuous change (e.g. so-called lust boys – puer delicatus, but also with regard to prostitution, extramarital relationships, polyamory etc.).

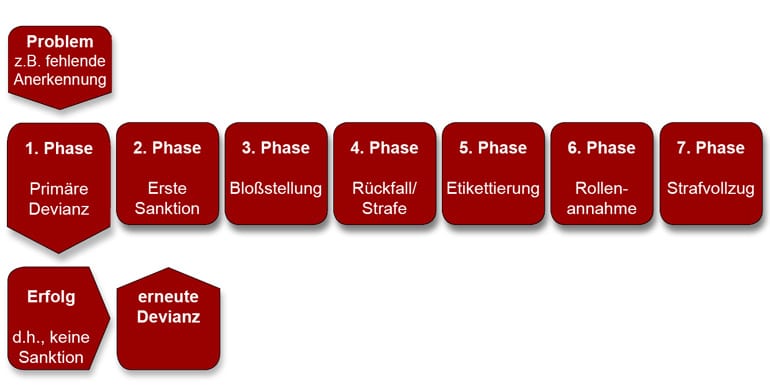

This perspective on crime as socially constructed is particularly widespread in so-called critical criminology. In contrast to an etiological perspective in the tradition of the Lombrosian project (see above), scholars developed the so called labelling approch in 1950s and 60s. Here, crime is not seen as a consequence of an individual pathology, but rather as a focus on criminalizing deviant behaviour.

Introductory literature

- Bruinsma, G. & Weisburd, D. (2014) Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. New York u.a.: Springer.

- Garland, D. (2002) Of crime and criminals : The development of criminology in Britain . In: Maguire, M.; Morgan, R. & Reiner, R. (Hrsg.) The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (3. Aufl.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hayward, K., Maruna, S., & Money, J. (Hrsg.). (2010). Fifty Key Thinkers in Criminology. New York: Routledge.

- Newburn, T. (2017) Criminology (3. Aufl.). London, New York: Routledge.