Cesare Lombroso’s anthropological theory of crime assumes that crime is genetic in nature. Lombroso in particular assumes that this is an atavistic type of criminal.

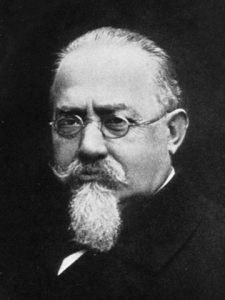

Main proponent

Theory

Genetic theories and research projects that deal with crime can be found mainly in Italy in the 19th century, in German history until 1945, but occasionally also in the present day. The founder and main representative of this approach is the Italian physician and psychiatrist Cesare Lombroso with his anthropological theory of crime.

The core thesis of his theory is the assumption of the born criminal. Accordingly, there is the criminal whose deviant behavior is inevitable. The criminal is not able to decide for or against a crime, but he acts completely unfree and determined. This biological determinism is contrary to the assumption of the classical school of criminology (according to which every human being is rational and has a rational freedom of choice and action).

Lombroso is also considered one of the main representatives of the Italian positive (or scientific) school of criminology. This positive school of criminology advocated biological positivism, i.e., the representatives demanded that criminological-scientific knowledge be based on empirically founded assumptions. Cesare Lombroso, who was a prison doctor and forensic physician, conducted countless investigations on prisoners and patients in psychiatric institutions. His research was influenced by the British naturalist and evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin (On the Origin of Species) and the German physician Franz Joseph Gall, among others. Gall is considered the founder of craniology, according to which human characteristics and mental faculties can be read in the shape and size of the skull and brain.

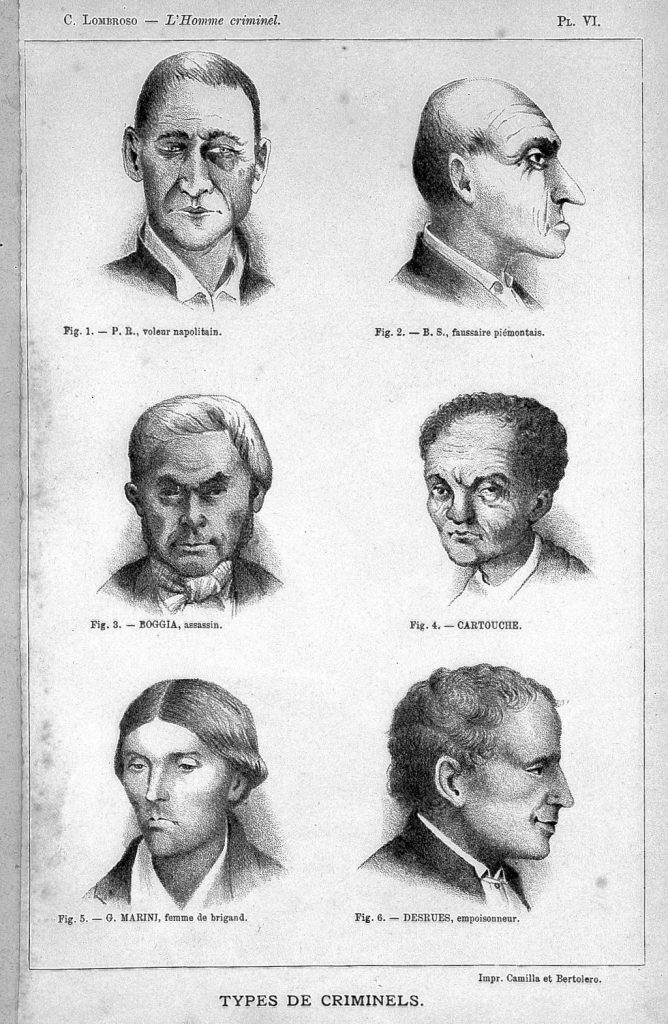

Lombroso published the results of his investigations in his main work “L’Uomo Delinquente” (The Criminal Man), first published in 1876. Numerous illustrations illustrate his research work. Certain body characteristics and skull shapes are associated with certain types of criminals and crimes.

The influence of evolutionary biology on Lombroso’s work is evident in the conviction that the criminal represents a distinct anthropological type, the “homo delinquens”. This type is atavistic, that is, a former and more primitive type of human being who has regressed in evolution, who is immoral and driven by instincts. He is lazy, insensitive to pain, vain, has cross-eyed eyes, a preference for tattoos, a receding forehead, a small brain, uses “crooked language” and so on.

In his early works, Lombroso attributes any crime to this atavistic type of person. Under the influence of French criminology, but also through his own students Garofalo and Ferri, Lombroso later relativized his initial thesis. Only about one third of all criminals are born criminals. For the remaining criminals, illness, environment and opportunity were decisive.

Schneider (2014; p. 322) summarizes Cesare Lombroso’s anthropological (anthropogenetic) theory of crime in four core statements:

- The criminal can be distinguished from the non-criminal by numerous physical and psychological anomalies.

- The criminal is a variety of the human species, an anthropological type, a degenerative phenomenon.

- The criminal is an atavism, a “degeneration” to a primitive, subhuman type of human being. Criminals are modern “savages”, physical and mental setbacks to an earlier stage of human history, to phylogenetic past. Criminals display physical and psychological characteristics that were believed to have been overcome in the history of development.

- Crime is inherited; it arises from a criminal disposition.

Implication for criminal policy

In terms of criminal policy, Lombroso’s theory can be described as extremely drastic.

Initially, Lombroso’s demand on criminal policy was that criminal law decisions be oriented and based on empirical and medical research. According to Lombroso, it must become clear that the notion of free choice (as demanded by representatives of the classical school of criminology) is not tenable and thus cannot be transferred to criminal law.

Since the offender is biologically and genetically determined in his actions, criminal deterrence (as propagated by representatives of the classical school of criminology) no longer plays a role. Even the greatest possible threat of punishment could no longer prevent the unavoidable act. The perpetrator did not freely choose the deviant act, but was involuntarily determined to do so by his biological constitution or – to stay with Lombroso – by his genetic makeup. Crime would therefore be fate, inevitable, and thus would not be the perpetrator’s own responsibility. Lombroso therefore advocated a punishment that is not objectively measured by the severity of the crime, but by the individually determinable danger of the perpetrator.

The anthropological theory thus raises the question of guilt: Can someone whose genes determine him to act unlawfully, who in Lomboz’s view has an innate physical and psychological degeneration, be held responsible for his actions?Lombroso and other followers of anthropological approaches have answered this question in the affirmative, since the protection of society takes precedence over the protection of the guiltless criminal (cf. Lombroso, 2006, p. 13). The main focus of crime prevention must therefore be less on deterrence and individual punishment than on protecting society by influencing the opportunities for crime and keeping incorrigible criminals away. Lombroso therefore advocated that born as well as habitual criminals should be locked up permanently in “prisons for the incorrigible”. In the fifth edition of “L’Uomo Delinquente”, Lombroso also withdraws from his original opposition to the death penalty. Born criminals who were accused of particularly cruel deeds as well as gang members accused of crimes endangering the state were to be executed. Lombroso rejected possible moral concerns because the born criminal was “programmed” to cause harm and was an atavistic reproduction not of a savage but of a brutal predator and vermin (Lombroso, 2006, p. 15).

The following table contrasts the paradigm shift from the transition of the classical school of criminology to biological positivism:

| Classicism | Positivism | |

|---|---|---|

| Object of study | The offence | The offender |

| Nature of the offender | Free-willed Rational, calculating Normal | Determined Driven by biological, psychological or other influences Pathological |

| Response to crime | Punishment Proportionate to the offence | Treatment Indeterminate, depending on individual circumstances |

(White and Haines (2004), here cited after Newburn, 2017, p. 132)

These Social Darwinist ideas fell on fertile ground in National Socialist Germany and were further perverted and abused in the course of eugenics and so-called racial hygiene: The incorrigibility of the delinquents was used to brand them once and for all as criminal men and to lock them away without hope of rehabilitation or kill them. Because of their dangerousness for society, these “genetic brutes” were destroyed or at least treated as pests of society without any leniency or humanity.

Specifically, in relation to the genetic “impurity” of those who were criminally predisposed, this led to the passing of laws that provided for sterilization, removal from society and mass destruction.

Critical appreciation & relevance

Today, Cesare Lombroso is considered the founder of a modern criminology because of the positivism he propagated. However, his anthropogenetic theory of crime presented here is considered obsolete. Nevertheless, the critical appraisal of Lombroso’s entire oeuvre is a complex undertaking [A good overview of the work history of “L’Uomo Delinquente” and a scientific-historical classification is provided by the editors of the English edition of the book in their detailed foreword (see Lombroso, 2006). Lombroso published more than thirty books and over a thousand essays in his lifetime. He expanded his main work “L’Uomo Delinquente” (The Criminal Man) from 252 pages of the first edition, which appeared in 1876, to a total of three volumes with nearly two thousand pages in the fifth edition, which appeared 20 years later. Lombroso revised individual assumptions, so that depending on the underlying text, statements contradict each other. The concept of the “born criminal”, for example, is only introduced into the work in the third edition. Here the author estimates that 40 percent of all criminals belong to this category. In later editions and further works, Lombroso puts this proportion at only 33 percent.In his later publications he also deviates from a strict biological determinism and gives social environmental conditions a share in the explanation of crimes. At the same time, however, he changes his views regarding the death penalty for born criminals (see above).

From today’s perspective, Lombroso’s empirical work proves to be unsystematic and does not meet today’s scientific standards. The assumption of a “born criminal” as an evolutionary regression in human history seems downright ridiculous. Gibson and Hahn Rafter, however, point out in the foreword to the English complete edition of “Criminal Man” that Lombroso’s work did indeed correspond to the scientific standards of the 19th century (cf. Lombroso, 2006, p. 8f.). However, Lombroso drew false scientific conclusions from the empirical knowledge that was generally not very developed at the time. In addition, he often used materials from third parties without examining them in detail. The control groups that Lombroso used for verification (mainly soldiers he examined) were insufficient, since there were criminals among the soldiers, for example, but also wrongly convicted persons among the prison inmates examined.

Charles Goring, an English contemporary of Lombroso’s, was able to prove, on the basis of his own research of prison inmates (and persons from a control group) in England, that criminals do not show significant differences in physical characteristics from non-criminals (see Goring, 1913). Other contemporaries of Cesare Lombroso also clearly criticized his theory during his lifetime (among the critics are such prominent names as Edwin Sutherland or the French criminologist Gabriel Tarde).

Lombroso’s anthropogenetic theory (and also its extensions in the German Reich as well as in the Weimar Republic) must be viewed extremely critically, first and foremost because of its role as scientific justification for the Nazis and their fascist ideology. Lombroso’s and related theories allow the conclusion that the criminal could be “abandoned” and thus be separated from society once and for all or treated (inhumanly) in some other way. This form of absolute distinction between criminal and non-criminal is politically extremely problematic, since it denies the offender any chance of recovery, resocialization, reparation or received forgiveness.

Regardless of the fact that Lombroso and his theory was widely criticized during his lifetime, the influence of the positive criminological school is still present today. Newburn describes this influence with reference to Garland (2002) as the “Lombrosian project” (2017, p. 4). According to this, modern criminology is a product of studies that, following Lombroso, investigate characteristics of criminals and non-criminals in order to get to the root causes of crime based on postulated differences between these groups.

This etiological paradigm proved to be particularly effective for German criminology and at times led to a split of the discipline into the camps of critical criminologists, who rejected any form of etiology, and the camp of those who must be considered part of the Lombrosian project.

Even today, there is still a branch of research that tries to explain crimes by using biology. Of course, today’s work no longer assumes a biological deterministic atavism. The attempt to calculate probabilities, risk factors and antisocial predispositions can, however, be understood in the same line of development as Lombroso’s work.

A final judgement on Cesare Lombroso and his scientific life’s work must be considered in a differentiated way. His scientific claim to criminological research makes him the founder of a modern empirical criminology. It must also be acknowledged that Lombroso was willing to expand his biological attempts at explanation by environmental and social aspects. It is therefore wrong to interpret him – as has often happened – exclusively as a radical representative of a determistic, biological school. Lombroso, who was himself a Jew, would certainly not have approved of the misuse of his research by German (and Italian) Nazism. Nevertheless, the thesis of the born criminal, popular at the time, prepared a broad stage for racist ideas.

Literature

Primary literature

- Lombroso, C. (2006). Criminal Man (translated and with a new introduction by Mary Gibson and Nicole Hahn Rafter). Durham; London: Duke University Press.

Secondary literature

- Bradley, K. (2010). Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909). In: Keith Hayward, Shadd Maruna & Jayne Mooney (Hrsg.). Fifty Key Thinkers in Criminology. London; New York: Routledge. S. 25-29.

- Gibson, M. (2002). Born to crime: Cesare Lombroso and the origins of biological criminology. Westport.

- Goring, C. (1913). The English Convict: a statistical study. London: HMSO.

- Newburn, T. (2017). Criminology (3. Auflage). London; New York: Routledge.

- Schneider, H. J. (2014). Kriminologie. Ein Internationales Handbuch [Band 1: Grundlagen]. Berlin; Boston: de Gruyter.