“Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City” is a book by sociologist Elijah Anderson that examines the dynamics of inner-city life in poor African American neighborhoods. Anderson conducted extensive field research in Philadelphia, focusing on the Code of the Street as a set of norms that exists among residents. The Code of the Street is a manifestation of social structures and it influences the interactions of the residents.

Main proponent

Theory

Anderson argues that the code of the street is characterized by respect and prestige, in which individuals must prove their toughness and maintain their social reputation. This often includes aggressive behavior, violence, and disrespect for authority. The code also emphasizes the need to present oneself as strong and fearless, even in the face of adversity.

Anderson (1999, p. 33) writes:

This is because the street culture has evolved a ‘code of the street,’ which amounts to a set of informal rules governing interpersonal public behavior, particularly violence. The rules prescribe both proper comportment and the proper way to respond if challenged. They regulate the use of violence and so supply a rationale allowing those who are inclined to aggression to precipitate violent encounters in an approved way. The rules have been established and are enforced mainly by the street-oriented; but on the streets the distinction between street and decent is often irrelevant.

The book examines how the code affects various aspects of life, including family dynamics, neighborhood interactions, and the educational system. Anderson discusses the challenges faced by young people trying to conform to the code while trying to succeed in school and avoid the pitfalls of street life.

In addition, Anderson addresses the impact of the code on the community’s relationship with law enforcement. He highlights the strained relationships between residents and law enforcement and the role the code plays in shaping those relationships.

Through his research, Anderson ultimately aims to illuminate the complex social dynamics and challenges faced by people living in impoverished neighborhoods and provide insight into the mechanisms that perpetuate a cycle of violence, street culture, and limited opportunities for social mobility.

Decent vs. Street

Central to Anderson’s book are the terms “decent” and “street,” which represent contrasting moral and normative orientations in disadvantaged African American neighborhoods.

decent: The term “decent” refers to individuals who adhere to conventional, middle-class social norms and values, including respect for authority, education, and hard work. Decent people strive to take advantage of legitimate opportunities and maintain positive relationships with others. They value adherence to social norms and seek to distance themselves from street culture. They value education, seek legal employment, and emphasize the importance of a stable family.

street: The term “street” refers to individuals who adopt a different set of values and behaviors within the code of the street. Those who join the street culture often face limited opportunities, economic hardships, and a sense of social exclusion. They adopt strategies and behaviors based on the need to prove their toughness, protect their reputation, and overcome the challenges of their environment. This may include aggressive behavior, defiance of authority, and resorting to street justice.

Anderson argues that the code of the street emerged in response to lack of economic opportunity, systemic racism, and social disorganization. It represents a set of alternative values and behaviors that residents adopt to survive and navigate their difficult situations. The code of the street often clashes with the conventional norms and values associated with a “decent” orientation.

It is important to note that these categories are not absolute or mutually exclusive. Anderson emphasizes that individuals can swing back and forth between the “decent” and “street” orientations depending on their circumstances and the social contexts in which they find themselves (code switch). The concepts of “decent” and “street” provide analytical tools for understanding the diversity of moral orientations and behaviors within disadvantaged communities.

What is the “Code of the Street”?

The term “code of the street,” describes a set of informal rules and behaviors that apply in disadvantaged African American neighborhoods, particularly in urban areas.

This set of specific norms provides a social framework that governs the interactions and behavior of residents in these communities. It is characterized by a culture of respect, respectability, and survival in the face of difficult circumstances such as poverty, limited opportunity, and social disorganization.

Anderson (1999, p. 33) writes:

At the heart of the code is the issue of respect—loosely defined as being treated ‘right’ or being granted one’s ‘props’ (or proper due) or the deference one deserves.

Some of the key elements of the Code of the Street are:

- Respect and reputation: Residents are expected to gain respect and maintain their reputation by demonstrating toughness and credibility on the streets. This often includes strength, fearlessness, and the ability to defend oneself.

- Street Justice: The code emphasizes resolving conflicts on one’s own and not relying on formal authorities. It encourages self-protection and retaliation when one’s reputation or honor is threatened.

- Demonstration of authority: Individuals are expected to assert their power and dominance in interactions, often through displays of aggression and intimidation. The code emphasizes the need to establish oneself as someone not to be trifled with.

- Materialism and status: Acquiring material possessions and flaunting wealth or success are seen in the street code as indicators of respect and status. This can lead to a focus on materialistic pursuits and activities involving illegal or illicit means of obtaining resources.

- Street socialization: The code is passed and reinforced through socialization processes within the community, especially among young people. They learn to manage the expectations of the code and adopt behaviors consistent with street culture.

It is important to note that the code of the street does not apply to all African American communities, nor does it apply to every individual in these neighborhoods. It is a sociological concept that aims to understand and analyze the cultural norms and social dynamics in specific contexts.

Implication for criminal policy

Elijah Anderson’s “Code of the Street” is initially not a typical criminological theory of crime, but the result of a sociological, ethnographic study of disadvantaged communities. The reference to crime (especially violent and drug-related crime) is nevertheless obvious. Clear references to several criminological theories will be outlined in the following:

Social Disorganization Theory: Anderson’s analysis of the code of the street is consistent with social disorganization theory. Both perspectives emphasize the impact of neighborhood characteristics such as poverty, housing instability, and lack of social cohesion on crime rates. Social disorganization theory states that these factors contribute to the breakdown of social control mechanisms and the occurrence of deviant behavior.

Subculture theory: Anderson’s concept is consistent with subculture theories, particularly those that examine the formation of deviant subcultures in response to structural constraints. Subculture theories assume that marginalized groups develop their own norms, values, and behaviors that are at odds with the social norms of mainstream society. The street code described by Anderson can be seen as the result of a subculture emerging in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Cultural Criminology: Anderson’s work is also associated with Kriminalität und soziale Kontrolle als kulturell geprägte Phänomene versteht und analysiert. Im Fokus stehen die Bedeutungen, Symbole und gesellschaftlichen Diskurse, die Kriminalität umgeben.">Cultural Criminology, a theoretical perspective that emphasizes the role of culture, meanings, and symbolic representations in shaping criminal behavior. Criminologists, considered proponents and adherents of Cultural Criminology, argue that crime and deviance are not only determined by structural factors, but are also influenced by cultural dynamics, including subcultural values, rituals, and symbols.

Labeling Theory: Anderson’s research relates to labeling theory, which examines the process by which individuals are labeled as deviant and how this labeling affects their self-identity and future behavior. The code of the street can be seen as a response to the stigmatization and negative labeling of individuals from disadvantaged communities.

It is important to note that Anderson’s work is not exclusively guided by any one theory, but draws insights from multiple perspectives to provide a comprehensive understanding of the social and cultural dynamics of disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Beyond these theoretical points of connection, Anderson’s work has multiple possible implications for the design of crime policy. Here, for example, one might think of:

Community engagement and empowerment: Anderson’s research highlights the importance of community dynamics and the influence of social relationships on behavior. Crime policies should prioritize community engagement and empowerment. This can be achieved through initiatives such as community policing, restorative justice programs, and community-led crime prevention. By involving communities in the decision-making process and empowering them to address local problems, policies can foster a sense of ownership, trust, and social cohesion.

Addressing the root causes of crime: Anderson’s work underscores that the Code of the Street is rooted in structural factors. Effective crime policy should therefore prioritize underlying causes such as social inequality, poverty, exclusion, experiences of racism and discrimination, etc., rather than focusing solely on punitive measures. Additionally, measures to promote education, job creation, economic development, and social services can provide individuals with viable alternatives to street culture and reduce the factors that contribute to criminal behavior.

Rehabilitation and reintegration: Because the street code is often perpetuated by a cycle of violence and limited opportunities, policies should prioritize rehabilitation and reintegration efforts. This includes access to education, job training, mental health services, and substance abuse treatment within the criminal justice system. By helping individuals transition from street culture to a more positive and productive lifestyle, policies can reduce recidivism and promote successful reintegration into society.

Raising Awareness of Prejudice and Cultural Competence: Anderson’s research underscores the need for criminal justice policies that address prejudice and cultural differences. Policymakers should promote awareness of ethnic and cultural differences within the criminal justice system and ensure that law enforcement and criminal justice professionals are trained in bias awareness and cultural competency. By promoting fair and equitable treatment, policies can help build trust between communities and the criminal justice system.

Collaboration and cross-sector partnerships: Anderson’s work underscores the complexity of the issues surrounding the street code, which requires a collaborative approach involving multiple stakeholders. Crime policies should encourage cross-sector partnerships among law enforcement, community organizations, educational institutions, health care providers, and other relevant sectors. By working together, policymakers can leverage diverse resources, expertise, and perspectives to develop comprehensive and effective strategies for addressing the code of the street.

Critical appreciation & relevance

Since its publication, “Code of the Street” has been widely received and Anderson has received several awards for his work. This includes not only the work discussed here, but numerous other publications on the subject (see, e.g., Anderson, 1990).

The author received the prestigious Stockholm Prize in Criminology in 2021. The statement in the judgment reads:

The research conducted by 2021 Stockholm Criminology laureate, Elijah Anderson, has considerably improved our understanding of the dynamics of interactions among young men and women that lead to violence, even among good friends. His years of immersion in street life in Chicago and Philadelphia provide a social microscope for understanding the consequences of prejudice and blocked opportunities through the eyes of people growing up in those areas. His widely-acclaimed books have attracted a wide readership and substantial scholarly influence, as his work has become a key link in the chaining of understanding high rates of violence in specific neighborhoods.

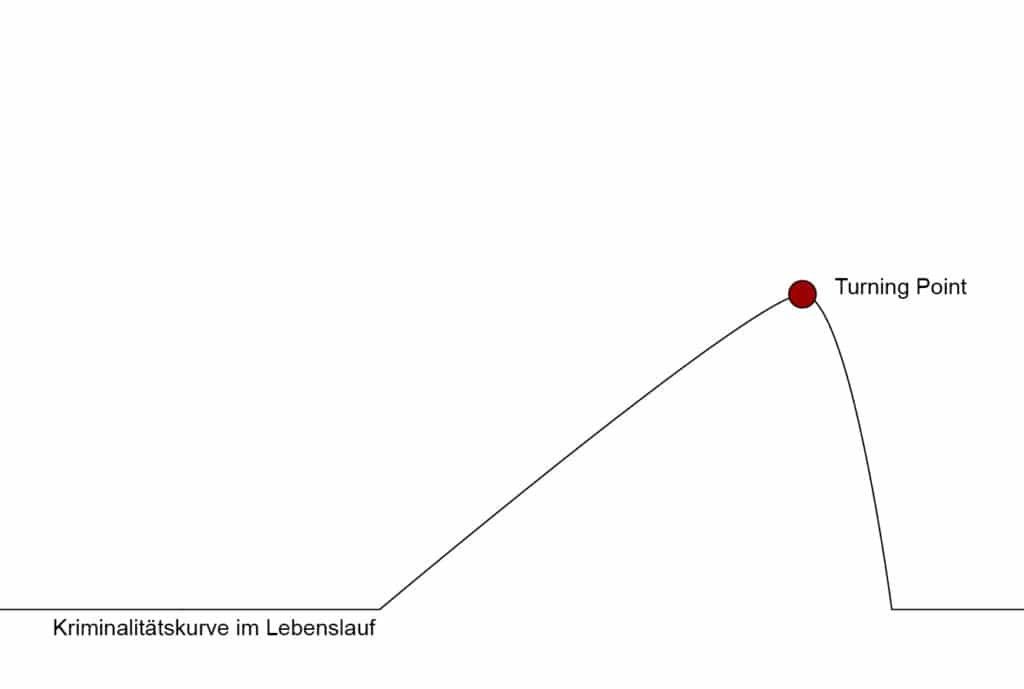

One circumstance that particularly distinguishes Anderson’s work is the underlying ethnographic research. Other well-known theories of crime are based solely on theoretical considerations and have at best been empirically tested years after the first publication (e.g., Merton’s anomie theory) or are based on quantitative studies (e.g., Sampson & Laub’s Turning Point Theory). Anderson’s work is based on extensive field research and interviews that provide a rich empirical foundation for understanding the street code and its effects. This empirical approach strengthens the credibility and reliability of the book’s findings. In recent years, the assumptions have also been tested many times in the course of other research (see, e.g., Brezina, 2004; Heitmeyer et al., 2019).

Specifically, it can be emphasized that Anderson’s work provides a deeper understanding of the dynamics of urban crime. Anderson’s research offers a nuanced understanding of the social dynamics in impoverished African American neighborhoods and their relationship to crime. By examining the code of the street, he illuminates how social and cultural factors influence the prevalence of violence and criminal behavior in these communities.

In addition, the work provides insights into the role of informal social control. The book examines how the street code serves as a form of informal social control in these neighborhoods. Understanding the mechanisms of informal social control is critical for criminologists to understand how communities self-regulate and maintain order in the absence of formal institutions.

“Code of the Street” looks at how ethnicity, social location, and crime influence each other and offers valuable insights into the experiences and challenges faced by marginalized communities. It emphasizes the impact of systemic factors such as poverty, discrimination, and limited opportunities on criminal behavior and the perpetuation of street culture.

Finally, Anderson’s work captures the zeitgeist. Numerous parallels can be drawn with pop-cultural phenomena, especially hip-hop culture. The street code described by Anderson, with its emphasis on respect, the willingness to assert one’s own claims by force, materialism, and the accompanying rejection of state authority, is a motif that is widespread in hip-hop culture and here especially in (gangsta) rap (and was long before Anderson’s book was published). In this context, reference should be made to the song Code of the Street (Gang Starr, 1994), in whose lyrics many of the motifs described can be found. A detailed account of the connection between Anderson’s work and the street culture portrayed in rap can be found in the work of Kubrin (2005).

Criticisms that could be raised are that Anderson’s analysis of street code overgeneralizes and is not applicable to all disadvantaged African American communities. Critics argue that the book focuses primarily on a specific subset of neighborhoods and may not fully capture the diversity of experiences and cultural differences within these communities.

In addition, it could be criticized that Anderson’s work offers only a limited understanding of violence, focusing primarily on interpersonal violence in disadvantaged communities. Critics argue that a more nuanced examination should also consider the structural violence that arises from systemic factors such as institutional racism and unequal access to resources.

Finally, as part of a critical assessment, it could be pointed out that the work may encourage stigmatization and negative stereotyping of African American communities. Thus, it could be argued that the focus on street culture and violence could reinforce harmful perceptions and contribute to the marginalization of these communities, rather than promoting a more holistic understanding of their challenges and strengths.

Literature

Primary literature

- Anderson, E. (2000). Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. W. W. Norton & Company.

Secondary literature

- Anderson, E. (1990). Streetwise. Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Community. The University of Chicago Press.

- Brezina, T. (2004). The Code of the Street: A Quantitative Assessment of Elijah Anderson’s Subculture of Violence Thesis and Its Contribution to Youth Violence Research. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(4), 303–328. doi:10.1177/1541204004267780

- Heitmeyer, W.; Howell, S.; Kurtenbach, S.; Rauf, A.; Zaman, M.; Zdun, S. (2019). The Codes of the Street in Risky Neighborhoods. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Youth Violence in Germany, Pakistan, and South Africa. Cham: Springer.

- Kubrin, C. E. (2005). Gangstas, Thugs, and Hustlas: Identity and the Code of the Street in Rap Music. Social Problems (52/3 ). S. 360-378.

Further Information

- Personal website of Elijah Anderson: http://elijahanderson.com/

Video

Street Codes – Code of the Street, Elijah Anderson

Elijah Anderson – Code of the Street

Gang Starr – Code of the Street (1994)

Song lyric of Code of the Street (Gang Starr, 1994) at Genius.com

The cover image shows a section of Philadelphia city map around Germantown Avenue, where Anderson conducted his ethnographic research. Source: OpenStreetMap