Cultural criminology is not a crime theory in the narrower sense. Rather, it is a theoretical current that has emerged in the English-speaking world and, based on cultural studies and critical theories of criminality, understands deviance and phenomena of crime control as an interactionist, symbol-mediated process and analyses them with recourse to primarily ethnological research methods.

Main proponents

Jeff Ferrell, Mike Presdee, Keith Hayward, Jock Young

Theory

Cultural Criminology examines and describes crime and forms of crime control as cultural products. Criminality and actors in crime control are understood as creative constructs that find expression in symbolically mediated cultural practices. Members of subcultures, control agents, politicians, state and private security agencies, media producers and recipients, commercial enterprises, and other social actors attribute meanings to these cultural practices that become the meaningful and justifying basis for their own actions. Cultural criminology sees its task in the analysis of this never-ending process of interpretation, reinterpretation and de-construction. Kriminalität und soziale Kontrolle als kulturell geprägte Phänomene versteht und analysiert. Im Fokus stehen die Bedeutungen, Symbole und gesellschaftlichen Diskurse, die Kriminalität umgeben.">Cultural Criminology does not see itself as a theory of crime in the narrower sense, but rather as a paradigm or perspective approach to phenomena of crime and criminalization, paying particular attention to images, symbols, representations and self-staging.

In analogy to Cultural Studies’ claim to point out and analyse the reciprocal, symbol-mediated relationships between actors, Cultural Criminology is located as a qualitatively oriented social science that draws on the methods of ethnography and textual and content analysis (see: Ferrell, 1995):

- Crime as Culture

Deviante subcultures are characterised by a system of symbols (slang expressions, appearance, style – “stylized presentation of self” – Ferrell, 1999). Belonging to a subculture requires the ability to construct and deconstruct this system of collective codes and practices. In addition, symbolic communication often takes place outside face-to-face interactions (e.g. hackers, graffiti sprayers, drug couriers, etc.). - Culture as Crime

This thematic area includes the criminalisation of cultural products and artists. The analysis focuses on the one hand on the distinction between so-called high culture (i.e. forms of culture that are primarily popular with the dominant social classes) and popular culture on the other. The criminalization of cultural products and forms mainly affects popular culture. However, there are isolated examples where criminalization also affects art products of so-called high culture (e.g. photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe and Jock Sturges are branded as pornographic). On the other hand, this stigmatization and criminalization mainly affects artists who belong to social minorities or subcultures (e.g. punk musicians, black rap musicians, gay and lesbian artists, etc.). - Media Constructions of Crime and Crime Control

This third major thematic focus and is dedicated to the analysis of the reciprocal mechanisms of action of the media and the judicial system.Building on the works of Howard S. Becker on “Moral Entrepreneurship” (1963) and Albert Cohen (1972/1980) on his concept of moral panics and the construction of folk devils, media coverage of crime phenomena is analysed. The interdependence of the media and law enforcement agencies is at the centre of this analysis. While the media are based on statements and data provided by police and courts, the media reports resulting from this information convey the delivered (desired) reading. In addition, this relationship of dependency plays a role in relation to agenda setting, i.e. the determination of which crime phenomena are given news value and – equally relevant – to which phenomena and events no media attention is paid. As a final aspect in this thematic focus, to which cultural criminology pays specific attention, the media construction of crime as an entertainment product must be mentioned. - Political dimension of culture, crime and cultural criminology

The fourth major thematic area, Cultural Criminology, is dedicated to the analysis of power relations in which media, social control, culture and crime stand:Deviant subcultures become the object of stately surveillance and control or are subject to a process of commodification and become the object of hegemonic culture.In “cultural wars”, the alternative art establishment and established artists argue about the aesthetic value of the works, declare alternative art a crime, and take action against the artists. The censorship of politically motivated artists represents the extreme case of these arguments about the hegemonic interpretation of aesthetics.Mass media succeeds in focusing on crimes and forms of social control by focusing on or, alternatively, ignoring certain themes. In an alliance with the state system of crime control, thematic fields are trivialized or dramatized, thus supporting a desired discourse/political agenda.The television landscape constructs “hundreds of tiny theatres of punishment” (after Focault in Cohen 1979: 339) in reality shows, court documentaries and crime series, in which ethnic minorities, followers of youthful subcultures, gays and lesbians play the villains who deserve just punishment.Cultural Criminolgy makes the subcultural counter-movements the subject of discussion, in which social criticism and resistance are shown and which in turn are the subject of counter-movements (resistance as counter-movement to hegemonic culture but also as thrill-seeking activity).

Key terms of Cultural Criminology

Transgression/ Carneval of Crime/ Edgework

In almost all societies one finds ritualized and to varying degrees institutionalized forms of excess. From the celebration of Osiris in ancient Egypt, to the Greek festival in honour of Dionysus, to celebrations in ancient Rome in honour of the deities Kalends and Saturnalia, to the carnival period still celebrated today (whose direct origins date back to the Middle Ages), all these festivities have in common that an institutionalised free sphere is created. During this fixed period of time, otherwise valid norms and power relations are abolished: Class differences, gender differences and the social order are turned upside down (fool becomes king, laymen preach as bishops, women storm the town hall and take over the government, etc.). All irrational, senseless and ordinary behaviour is legitimate and the participants do not have to fear sanctions.

The time of carnival is a time of delimitation, ecstasy and excess, facing the dominant attitude of limitation and reason. The authors of Cultural Criminology argue that these ritualized times of delimitation have lost their meaning and power in modern societies and can at best serve as a commodified confirmation of the ruling order.

Instead, postmodern societies have produced a series of cultural practices and activities that have a carnivalesque character (satire events on television, body modification, S&M practices, raves, consumption of soft drugs/ party drugs, gang rituals, festivals, extreme sports, partly also political demonstrations, joyrides (reclaim your streets) – activities are not originally carnivalesque but contain elements of performative pleasure and oppose the dominant attitude towards reason and sobriety.

Criminological verstehen

The concept of criminological Verstehen (Ferrell & Hamm, 1998) goes back to the German sociologist Max Weber (here: Verstehende Soziologie). At the centre of understanding (or interpretative) sociology/ criminology is social action. Social action is constitutive for social development. The focus is on the acting actors and their respective constructions of meaning that underlie their actions. The task of understanding or interpretive sociology/criminology is to analyse these subjective constructions of meaning and their deconstruction, taking into account the social and historical framework conditions.

Style

The term style refers to the sociological theoretical tradition of symbolic interactionism (George H. Mead). According to symbolic interactionism, interactions are characterized by symbols that express themselves primarily in social objects, relationships and situations. The symbols have no meaning as such. Only in interaction do social actors communicate through language, gestures and facial expressions about the interpretation and assignment of meaning to the symbols. The meaning of a symbol or the interpretation of the meaning structure of this symbol is synonymous with the adoption of values and motifs, which goes hand in hand with the socially predominant meaning structure of a symbol. Both the conferring of meaning (i.e. the construction of symbols) and the perception and decoding (i.e. the deconstruction) of symbols is learned in the course of the socialization of a member of society.

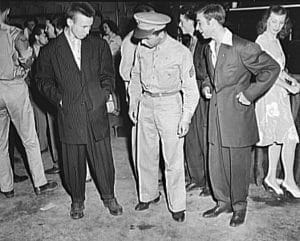

“Style” in the sense of Cultural Criminology could be described as a collection of symbols and their respective attribution of meaning. Above all (youthful) subcultures are characterized by a complex system of symbols and their shared attribution of meaning. Style is thus far more than just an aesthetic category. Belonging to the subculture rather requires knowledge about the meaning of the respective symbol and thus the ability to decipher this symbol according to the meaning ascribed within the subculture (e.g. the “reading” of graffiti, but also e.g. the meaning of certain sports and training jackets as a sign of a gang membership). The construction and meaning of symbols within a subculture often takes place in a conscious departure from the usual hegemonic attribution (e.g. the oversized suits of the “Zoot Suiter”, see illustration) and refers to the social situation of the subculture members and their attitudes towards systems of norms and values that are shared by the majority of society.

Implication for Criminal Policy

With the explicit reference to the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies and the tradition of (British) Critical Criminology (“New Criminology”), and not least to interactionist (American) sociology, the authors of Cultural Criminology place themselves in a left-wing political spectrum. In agreement with representatives of labeling theory, Marxist and feminist theories of crime (see: Conflict-oriented theories of crime), Cultural Criminology understands crime and crime control as the result and consequence of attribution processes. The main implication of this analysis in terms of criminal policy is a departure from the punitive turnaround in criminal policy. Instead of increasingly criminalizing and (increasingly harshly) punishing other persons (groups) and actions, the authors of Cultural Criminology advocate an understanding of socially marginalized groups and for more social justice.

Critical Appraisal & Relevance

Although cultural criminology does not claim to be a self-contained theorem, it is subject to various criticisms: the program is too vague, the methodological approach too arbitrary, crimes are played down, and integration with Marxist theories is inadequate. For a detailed discussion of this criticism, see e.g. Hayward, 2016 and Ilan, 2019.

Literature

Primary literature

- Ferrell, Jeff; Hayward, Keith J; Young, Jock (2008). Cultural criminology. An invitation. 1. publ. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Ferrell, Jeff (2007) Cultural Criminology. In: Ritzer, George (ed). Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Blackwell Publishing. Blackwell Reference Online.

- Ferrell, Jeff (2004). Cultural criminology unleashed. London: GlassHouse.

- Jeff Ferrell (1999). Cultural Criminology, Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 25, pp. 395-418

- Ferrell, Jeff; Hamm, Mark (eds) (1998). Ethnography at the edge: Crime, deviance, and field research. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Ferrell, Jeff; Sanders Clinton R. (1995). Cultural criminology. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

- Ferrell, Jeff (1995). Culture,Crime, and Cultural Criminology. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 3(2), S. 25-42. [Volltext]

- Hayward, Keith J. (2016). Cultural criminology: Script rewrites. Theoretical Criminology, 20(3), 297–321.

- Presdee, Mike (2001). Cultural criminology and the carnival of crime. Reprint. London: Routledge.

Secondary literature

- Hayward, Keith J (2010): Framing crime. Cultural criminology and the image. New York: Routledge-Cavendish.

- The journal “Crime, Media and Culture: an international Journal” provides an excellent insight into the manifold topics of cultural criminology.

Further Information

The website CulturalCriminology.org, maintained by the University of Kent, contains numerous references to publications, films, conferences and websites relevant to cultural criminology.