The Broken Windows Theory was developed by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. According to the two authors, the broken window must be repaired as quickly as possible to prevent further destruction in the neighborhood and an increase in the crime rate. Destruction in urban areas is therefore inextricably linked to crime and causes it. A seemingly harmless phenomenon can therefore have serious consequences.

Main proponents

George L. Kelling, James Q. Wilson

Theory

Wilson and Kelling had a major influence on the American policing strategies of the time. In their studies, they focused on police foot patrols as a method of policing. Although their studies proved that foot patrols had no effect on crime rates, they demonstrated that the presence of police made neighborhood residents feel safer. To illustrate their point of view, they developed the so-called Broken Windows Theory:

In the Broken Windows Theory, the authors refer to an experiment by the psychologist Philip Zimbardo (1969). He parked a car in the Bronx in New York and another in Palo Alto in California with the number plates removed and the bonnet open. In the Bronx, within minutes, residents began to dismantle usable parts of the car and then destroyed it completely. The car in Palo Alto, however, was left untouched. A concerned passer-by simply closed the open hood. It was only when Zimbardo intervened in the experiment and demolished the car himself with a sledgehammer that the car was finally cannibalised by local Californians. Zimbardo concluded that the vandalism was partly due to visible previous damage and partly to the experience of social disorder/neglect in the neighbourhood. He writes:

We might conclude from these preliminary studies that to initiate such acts of destructive vandalism, the necessary ingredients are the acquired feelings of anonymity provided by the life in a city like New York, along with some minimal releaser cues. Where social anonymity is not a “given” of one’s everyday life, it is necessary to have more extreme releaser cues, more explicit models for destruction and aggression, and physical anonymity—a large crowd or the darkness of the night.

(Zimbardo, 1969, S. 292)

Wilson and Kelling take up Zimbardo’s study results and conclude:

Untended property becomes fair game for people out for fun or plunder and even for people who ordinarily would not dream of doing such things and who probably consider themselves law-abiding. Because of the nature of community life in the Bronx—its anonymity, the frequency with which cars are abandoned and things are stolen or broken, the past experience of “no one caring”—vandalism begins much more quickly than it does in staid Palo Alto, where people have come to believe that private possessions are cared for, and that mischievous behavior is costly. But vandalism can occur anywhere once communal barriers—the sense of mutual regard and the obligations of civility—are lowered by actions that seem to signal that “no one cares.”

(Kelling & Wilson, 1982)

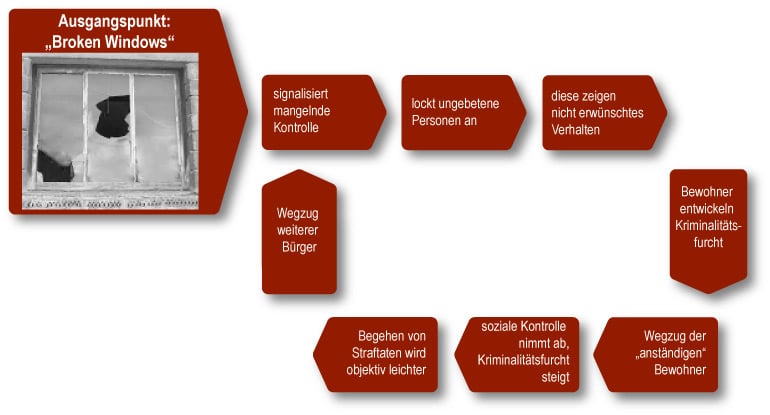

Following on from Zimbardo’s experiment, Wilson and Kelling apply the Broken Windows approach to signs of decay in social spaces. Wilson and Kelling see urban decay, such as broken windows, as a trigger for criminal behaviour. The broken windows symbolise dilapidated parts of the city. The visible decay signals a lack of control to the residents of the neighbourhood, which is also perceived by other (unwanted) visitors to the neighbourhood. The presence of these people and the signs of physical neglect fuel a fear of crime among long-time residents, who are now beginning to leave the area as a result of these changes. The departure of ‘decent citizens’ leads to a decline in social control, which objectively facilitates the commission of crime. More residents now leave the neighbourhood, setting in motion a virtuous circle.

Wilson and Kelling distinguish between signs of a lack of formal and informal social control (also known as incivilities):

- physical disorder (such as dilapidated buildings, abandoned properties, graffitied walls, etc.) and

- social disorder (stray groups on the streets, homeless people, aggressive beggars, drug scene, etc.).

Implications for Criminal Policy

Newly elected Mayor Rudolph Giuliani appointed William Bratton as Police Commissioner in 1994, and together they pursued a comprehensive crime reduction strategy that included zero-tolerance policing as a central element. Giuliani was a strong supporter and advocate of aggressive enforcement of low-level crime laws, emphasising the Broken Windows theory.

Zero tolerance policing in New York City involved cracking down on low-level offences such as fare evasion, public drunkenness and vandalism. The police focused on rigorously enforcing the law and making arrests for even minor violations. This approach was credited with a significant reduction in the city’s overall crime rate during this period.

However, the strategy was criticised for its potential to disproportionately affect minority communities and for the controversial use of stop-and-frisk tactics. Critics argued that the aggressive enforcement of minor offences led to the profiling of certain demographic groups, raising concerns about civil liberties and racial discrimination.

The implementation of zero-tolerance policing during the Giuliani administration was associated with a significant decline in crime rates in New York City, contributing to the perception that the strategy was successful. However, it also sparked debates about the ethical implications of aggressive policing tactics and their impact on certain communities.

Whether and to what extent zero-tolerance policing is successful is a matter of debate among criminologists. In fact, other major US cities experienced significant reductions in crime during the 1990s without using this policing strategy. This suggests that other factors, such as demographic changes and developments in the illegal drug market, were responsible for the drop in crime in New York City and other major cities. William Bratton later tried to build on his success in New York and became police commissioner in Los Angeles. However, zero-tolerance policing failed to bring about a significant reduction in crime.

Another implication of the Broken Windows Theory for crime policy would be to strengthen communities (e.g. through community policing) and to focus more on situational crime prevention.

Critical Appraisal & Relevance

The Broken Windows Theory is one of the best known and most cited of the criminological theories of crime. The success of the theory is undoubtedly due to its simple assumption of a causal relationship between public order and crime.

However, critics such as the American criminologists Sampson and Raudenbush (1999) argue that this assumed causal relationship is based on a false assumption. Rather, they argue that the postulated direct link between (dis)order and crime is mediated by the degree of social cohesion in a community and the shared expectation of social control in the residential environment. Representatives of cultural criminology argue in a similar vein, criticising that incivility is understood primarily as an aesthetic value judgement and that the explanatory link between social control and crime is often ignored. In addition, the assessment of phenomena described as disorder is more complex and ambiguous (e.g. graffiti).

The assumed link between incivility and fear of crime is also criticised, as the perception of disorder phenomena would be selective and primarily affect people who have a higher level of fear of crime to begin with. The argument is therefore tautological.

Zero tolerance policing has been, and continues to be, subject to fierce criticism. Critics such as Hess (2004) question the effectiveness of the policing method. They argue that other factors, particularly social factors, are responsible for the decline in crime in New York. Other critics complain that the policing method is racist and discriminatory, as socially disadvantaged non-white people in poorer neighbourhoods are particularly affected by the policing measures (see, for example, Harcourt, 2001).

Literature

Primary Literature

- Kelling, George L; Coles, Catherine M (1997): Fixing broken windows. Restoring order and reducing crime in our communities. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Kelling, George L.; Wilson, James Q. (1982): Broken Windows. The police and Neighborhood Safety. The Altlantic. [Volltext]

Secondary Literature

- Dreher, G.; Feltes, T. (Hrsg.) (1997). Das Modell New York: Kriminalprävention durch “Zero Tolerance”?: Beiträge zur aktuellen kriminalpolitischen Diskussion. Veröffentlicht in Empirische Polizeiforschung 12. Online verfügbar unter: https://publikationen.uni-tuebingen.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10900/78229/epf_12.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Harcourt, B. E. (2001). Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing. Harvard University Press.

- Hess, H. (2004): Broken Windows: Zur Diskussion um die Strategie des New York Police Department. Zeitschrift für die Gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft. Band 116, Heft 1, Seiten 66–110.

- Sampson, Robert J.; Raudenbush, Stephen W (1999): Systematic Social Observation of Public Spaces: A New Look at Disorder in Urban Neighborhoods. American Journal of Sociology. 105 (3): 603–651.

- Schwind, H.-D. (2008): Kriminologie. Eine praxisorientierte Einführung mit Beispielen. S. 326-330.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (1969). The Human Choice: Individuation, Reason, and Order versus Deindividuation, Impulse and Chaos. In: Arnold, W. J. & Levine, D. (Hrsg.). Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. S. 237-307.

Further Information

Videos

[YouTube Video: Broken Windows Theory – Criminology]